How Tiny Changes in DNA Packing Can Switch Genes On or Off

How does nearly two metres of DNA fit inside a cell nucleus just a few micrometres wide — and how does that same packing decide which genes a cell can use? A new study published in “Science” offers a striking answer: even a difference of just a few DNA “letters” in spacing can fundamentally change how our genome behaves.

Why DNA Packing Matters Beyond Storage

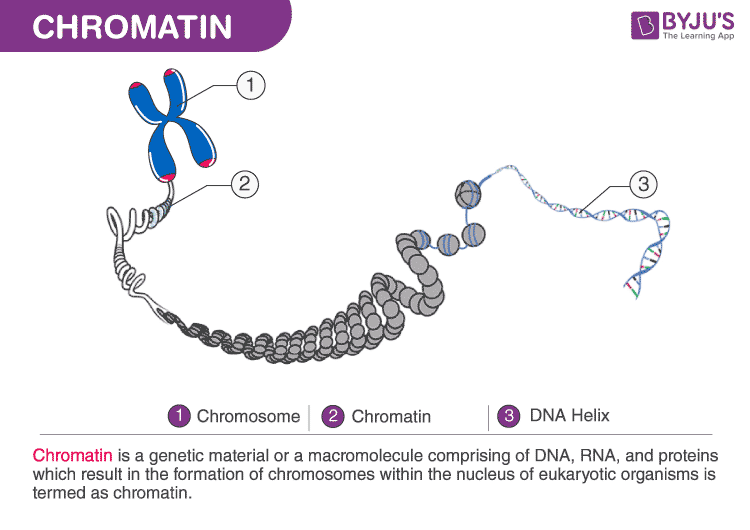

Inside human cells, DNA is not loose or floating freely. Instead, it is wrapped around bead-like proteins called histones, forming repeating units known as nucleosomes. These nucleosomes are connected by short stretches of exposed DNA, together forming a complex structure called chromatin.

This arrangement does more than save space. Chromatin’s physical organisation determines whether genes are accessible to the cellular machinery that reads them, or tightly packed and effectively switched off. Loosely organised regions tend to be active; densely packed regions are usually silent. How cells control this balance has been a central puzzle in molecular biology.

A Small Structural Detail with Big Consequences

The new study, led by Michael Rosen of the UT Southwestern Medical Center, shows that chromatin behaviour can change dramatically depending on the length of the DNA “linker” connecting one nucleosome to the next.

DNA is not a straight ladder but a twisted helix. Because of this, even tiny changes in linker length — as small as five DNA base pairs — alter how nucleosomes sit relative to one another. These orientation changes then ripple along the entire chromatin fibre, reshaping how it folds and interacts.

Building Chromatin from Scratch to Test the Idea

To isolate this effect, researchers recreated chromatin in the laboratory using identical DNA sequences and the same proteins, changing only the length of the linker DNA between nucleosomes. They compared fibres with slightly shorter linkers to those with slightly longer ones.

Using rapid freezing and high-resolution imaging, the team was able to directly visualise individual nucleosomes and track how chromatin clusters formed, merged, moved and broke apart — something that has been difficult to observe inside living cells.

Two Physical States, Two Very Different Behaviours

The results revealed a sharp divide. Chromatin with shorter linker DNA stayed more extended, with nucleosomes reaching outward and forming many connections with neighbouring strands. These clusters behaved like dense, elastic materials — slow to fuse and hard to break apart, similar to tangled yarn.

Chromatin with longer linkers folded inward instead, with nucleosomes interacting mostly within the same strand. This reduced inter-strand contacts, creating clusters that were more fluid, easier to merge, and simpler to dissolve. As Prof. Rosen described it, one system behaved like a simple liquid, while the other resembled toothpaste or silly putty.

Structure Emerging Without Genetic Instructions

Importantly, these differences emerged even though the DNA sequence and protein components were identical. What changed was purely the physical arrangement. According to Yamini Dalal of the National Institutes of Health, this reinforces a long-standing idea: chromatin is a self-organising system.

“The genome’s organisation is encoded in the chromatin itself,” she noted. No extra molecular instructions are required for structure to emerge — basic physical principles are enough.

Do These Rules Apply Inside Real Cells?

When the researchers examined chromatin from human and mouse cells, they found dense regions with packing patterns similar to those produced in the lab. This suggests that the same physical rules operate inside the nucleus.

However, whether cells deliberately fine-tune linker lengths to regulate gene activity remains an open question. Maintaining precise spacing differences across a constantly moving and remodelled genome would be challenging.

Why Repetitive DNA May Be Especially Vulnerable

Dr. Dalal cautioned that these effects may matter most in highly ordered genomic regions, such as repetitive DNA. In such regions, even small disruptions in chromatin packing could hinder the movement of regulatory molecules, making genes harder to access.

Disorder in repetitive chromatin is already linked to genome instability in ageing and cancer. The study provides a physical framework for understanding why these regions may be particularly fragile.

Implications for Gene Regulation and Cell Identity

From a broader perspective, the findings raise intriguing questions about gene regulation across different cell types. Sarah Teichmann of the Human Cell Atlas suggested that chromatin’s physical state itself could influence how genes behave in different cells.

Large-scale efforts like the Human Cell Atlas, which map molecular differences between cell types, could eventually test whether variations in chromatin physics help define cellular identity.

A Subtle Mechanism with Far-Reaching Impact

The study highlights how surprisingly small physical differences — just a few DNA building blocks — can reshape the genome’s architecture and behaviour. It suggests that gene regulation is not only a matter of chemical signals and genetic code, but also of mechanics and geometry.

As molecular biology increasingly intersects with physics, such insights may reshape how scientists understand development, disease and the ageing genome — revealing that sometimes, the smallest structural tweaks make the biggest biological difference.