Module 13. Sources, Historiography and Numismatics

The study of the past depends fundamentally on the examination, interpretation and evaluation of various sources. Historiography refers to the methodology and philosophy of historical writing, while numismatics, the study of coins and currency, provides tangible evidence that supports historical narratives. Together, these fields form an essential triad in reconstructing and understanding ancient, medieval and modern civilisations.

Nature and Classification of Historical Sources

Historical sources are the foundational materials from which historians reconstruct the past. They are broadly classified into primary and secondary sources.

- Primary sources are those produced during the period under study. They include inscriptions, manuscripts, coins, artefacts, monuments, official records, letters, and contemporary literary works. These provide direct, first-hand information about the events, cultures and societies of their time.

- Secondary sources, on the other hand, are later interpretations and analyses of primary data, often written by historians and scholars. These include modern histories, commentaries, biographies and academic articles.

Primary sources can further be divided into archaeological, literary and oral sources:

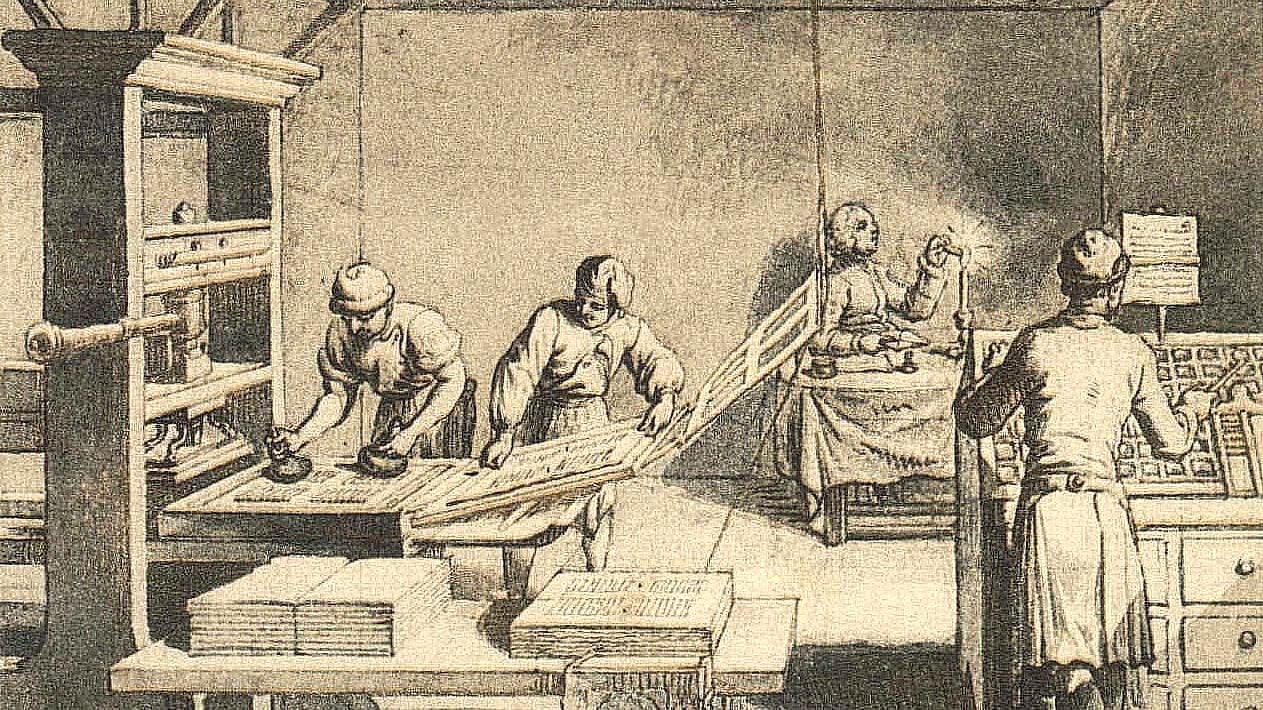

- Archaeological sources include artefacts, pottery, tools, sculptures, inscriptions and architectural remains discovered through excavation.

- Literary sources encompass religious texts, epics, chronicles, biographies and administrative documents.

- Oral sources include traditions, folklore, songs and myths passed down through generations, particularly valuable for regions with limited written records.

Historiography: Meaning and Evolution

Historiography refers to the study of how history has been written, interpreted and understood over time. It examines the perspectives, biases, and methodologies adopted by historians in different periods.

In ancient India, historical writing often took the form of dynastic chronicles and religious texts rather than analytical histories. Works such as the Rajatarangini by Kalhana in the twelfth century CE represent early attempts at systematic history writing, documenting the rulers of Kashmir with a critical approach.

In medieval Europe, historiography was deeply influenced by the Church, with monks and clerics recording events in annals and chronicles. The Renaissance ushered in a new era of secular historiography, with scholars such as Machiavelli adopting rational and political perspectives.

The modern period saw the emergence of professional historiography, driven by Enlightenment rationalism and the development of scientific methods. Historians such as Leopold von Ranke emphasised objectivity and the use of primary documents, arguing that history should describe events “as they actually happened.”

In the Indian context, modern historiography developed during the colonial period. British scholars like James Mill and Vincent Smith presented an imperial perspective, often dismissing indigenous traditions. In contrast, nationalist historians such as R.C. Majumdar and K.P. Jayaswal sought to reclaim India’s historical agency, while Marxist historians like D.D. Kosambi introduced socio-economic interpretations grounded in material conditions.

The Role of Numismatics in Historical Research

Numismatics, the scientific study of coins, plays a crucial role in historical reconstruction. Coins serve as both economic artefacts and historical documents, providing evidence about political authority, trade, economy, religion and art.

Coins are valuable because they are durable, datable and often inscribed with the names, titles and symbols of rulers. The imagery and legends on coins reveal much about political ideology, state religion and cultural exchanges. For instance, Indo-Greek coins often feature Hellenistic iconography combined with Indian motifs, illustrating cross-cultural interactions.

The study of coins helps historians in several ways:

- Political History: Coins bearing royal portraits and inscriptions confirm the existence and territorial extent of kingdoms. For example, the coins of the Gupta emperors are instrumental in reconstructing Gupta political history.

- Economic History: The metal content, weight and circulation of coins reveal information about trade networks, monetary systems and metallurgical knowledge. The widespread use of punch-marked coins in ancient India signifies the early development of a monetary economy.

- Religious and Cultural Insights: Depictions of deities, symbols, and rituals on coins reflect prevailing religious beliefs and artistic styles. The Kushana coins depicting the Buddha mark an important stage in the spread of Buddhism.

- Chronological Evidence: Coins often carry dates or stylistic features that enable precise chronological classification, aiding in synchronising dynastic timelines.

Integration of Sources and Interdisciplinary Approaches

Historians today employ an interdisciplinary approach, integrating various sources to obtain a more comprehensive understanding of the past. Archaeological evidence is analysed alongside literary accounts, and numismatic data is corroborated with epigraphic records. For instance, the reign of Emperor Ashoka is reconstructed through the study of his inscriptions (edicts), coins and references in Buddhist texts.

Modern technology further enhances historiographical and numismatic research. Radiocarbon dating, metallurgical analysis, and digital imaging help authenticate and date artefacts, while GIS mapping and statistical modelling allow scholars to trace trade routes and settlement patterns.

Critical Evaluation and Challenges in Historical Interpretation

While sources are indispensable, they must be critically examined. Every document, artefact or coin is a product of its context and may reflect the biases of its creators. For instance, royal inscriptions often exaggerate victories and virtues, serving as instruments of propaganda. Therefore, historical criticism involves assessing the authenticity, reliability and representativeness of each source.

Historians employ two main forms of criticism:

- External criticism, which verifies the genuineness of a source by analysing material aspects such as script, paper, ink, or metal composition.

- Internal criticism, which evaluates the credibility of the content by comparing facts, cross-referencing other sources and identifying inconsistencies.

Historiography itself faces the challenge of subjectivity, as historians are influenced by their social, political and intellectual contexts. Modern trends such as feminist historiography, subaltern studies and postcolonial criticism attempt to redress the marginalisation of certain voices in traditional narratives.

Significance of Sources, Historiography and Numismatics

The interplay between sources, historiography and numismatics forms the backbone of historical research. Sources provide the raw material; historiography offers interpretive frameworks; and numismatics contributes material and economic evidence. Together, they ensure that history remains both empirical and interpretive — grounded in evidence yet open to new readings.