Module 23. Economic and Social Developments Under British Rule

The period of British rule in India, extending from the mid-eighteenth century to 1947, brought about profound economic and social transformations. While the British introduced modern systems of administration, education, and communication, their policies were primarily designed to serve imperial interests. Consequently, India experienced both structural modernisation and severe economic exploitation. The interplay between colonial economic policies and social change fundamentally reshaped Indian society and laid the foundations of modern India.

Colonial Economic Policies and their Impact

The British economic policies in India were guided by mercantilist and later capitalist principles, designed to ensure Britain’s industrial supremacy. The colonial government restructured India’s traditional economy into a dependent, export-oriented system that catered to the needs of the British Empire.

-

Agrarian Policies and Land Revenue SystemsThe British transformed India’s agrarian economy by introducing new land revenue arrangements:

- Permanent Settlement (1793): Implemented in Bengal by Lord Cornwallis, it created a class of hereditary zamindars responsible for collecting revenue from peasants. This led to the growth of landlordism and the exploitation of cultivators.

- Ryotwari System: Introduced in Madras and Bombay Presidencies, it recognised individual cultivators (ryots) as landholders, who paid revenue directly to the state.

- Mahalwari System: Implemented in North-Western Provinces and parts of Central India, it made entire villages (mahals) collectively responsible for revenue.

These systems resulted in heavy taxation, rural indebtedness, and agricultural stagnation. Land became a marketable commodity, disrupting traditional land relations and leading to widespread peasant unrest.

-

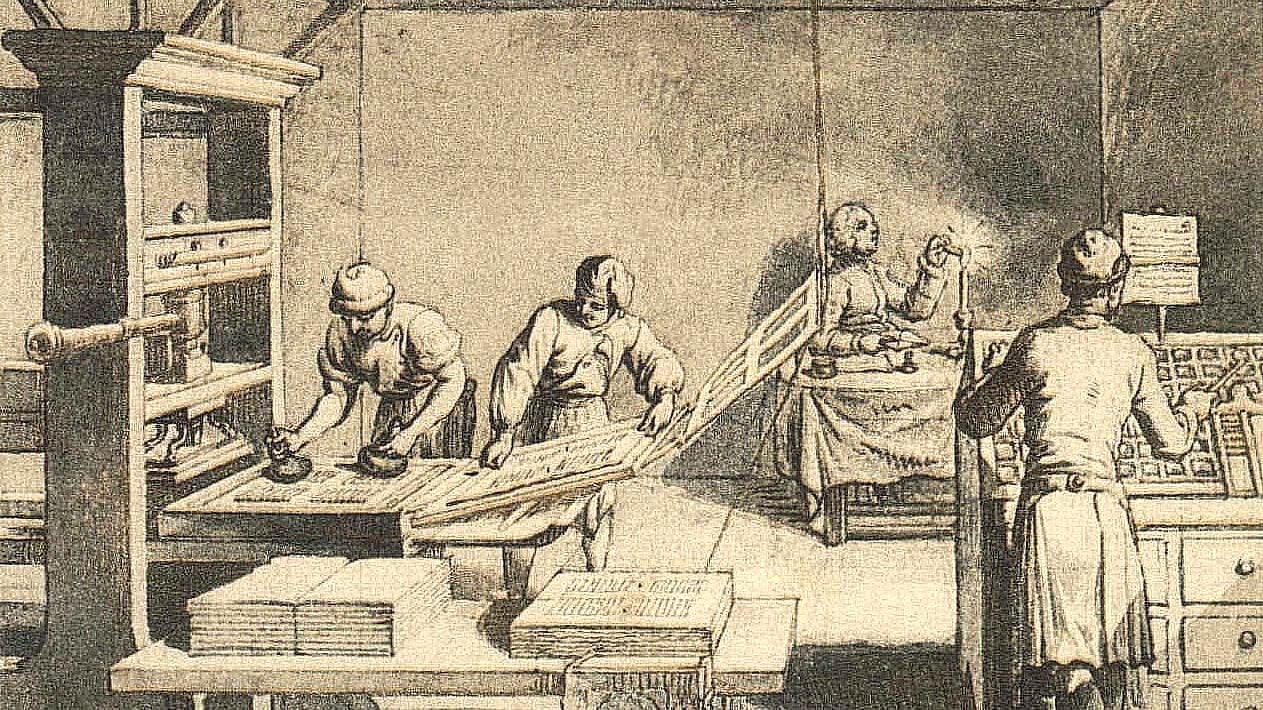

Deindustrialisation and the Decline of Indigenous IndustriesBefore British domination, India was known for its flourishing handicrafts, especially textiles. However, British industrialisation and free trade policies destroyed Indian artisanal production. Cheap machine-made British goods flooded the Indian market, while export duties on Indian goods restricted overseas trade.

The decline of traditional industries, combined with lack of state support, led to deindustrialisation and the impoverishment of artisan classes. By the nineteenth century, India had shifted from being an exporter of manufactured goods to an exporter of raw materials and importer of finished products. - Commercialisation of AgricultureUnder British influence, Indian agriculture was increasingly directed towards producing cash crops such as indigo, cotton, jute, tea, coffee, and opium for export. This commercialisation disrupted food grain production, contributing to famines and food insecurity. The dependence on global markets exposed Indian peasants to price fluctuations and indebtedness.

-

Infrastructure and Transport DevelopmentThe British introduced modern infrastructure primarily to serve economic and administrative interests.

- Railways (from 1853): Facilitated the movement of raw materials to ports and finished goods inland.

- Roads and Canals: Expanded to support trade and military mobility.

- Telegraphs and Postal Services: Improved communication and administrative efficiency.

Although these developments integrated the Indian market and promoted regional mobility, their benefits largely accrued to British capitalists.

-

Foreign Trade and the Drain of WealthIndia became a colonial appendage of British industry, supplying raw materials and consuming British products. The concept of the “Drain of Wealth”, articulated by Dadabhai Naoroji, described the unrequited transfer of Indian resources to Britain through trade surpluses, salaries of British officials, and interest on public debt.

This economic drain impoverished India while enriching Britain, contributing to underdevelopment and the lack of indigenous industrial capital.

Industrialisation and Modern Economic Developments

Despite the exploitative nature of British rule, the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed the beginnings of modern industries in India. Indian entrepreneurs such as Jamshedji Tata, Dwarkanath Tagore, and Dinshaw Petit established ventures in cotton textiles, jute, coal mining, and steel production.

The textile mills of Bombay, jute factories of Bengal, and the Tata Iron and Steel Company (1907) symbolised indigenous industrial initiative. However, industrial growth remained limited due to discriminatory colonial policies, lack of capital, and restricted domestic markets.

Banking institutions such as the Presidency Banks (established between 1806 and 1840) and later the Imperial Bank of India (1921) were founded to serve British commercial needs. Monetary policy and fiscal control further tied India’s economy to the British financial system.

Famines and Economic Distress

Recurrent famines during British rule reflected the vulnerability of the colonial agrarian economy. The Great Famine (1876–78), Orissa Famine (1866), and Bengal Famine (1943) resulted in millions of deaths. British adherence to laissez-faire economic policies prevented effective famine relief.

The Famine Commission Reports (1880 and 1901) highlighted the administrative negligence and recommended irrigation and food reserves, but these measures were insufficient. Famines exposed the exploitative and indifferent nature of colonial governance.

Social Transformations under British Rule

The British period witnessed far-reaching social changes, driven by Western education, legal reforms, and social movements. The interaction between traditional Indian society and Western ideas produced both conflict and reform.

-

Impact of Western EducationThe introduction of Western education through policies such as Macaulay’s Minute (1835) and Wood’s Despatch (1854) created a new English-educated middle class. Universities established in Calcutta, Bombay, and Madras (1857) became centres of intellectual development.

This class absorbed Western ideals of liberty, rationalism, and nationalism, later becoming the backbone of the Indian freedom movement. However, education remained limited in reach, and rural illiteracy persisted. -

Social and Religious Reform MovementsThe nineteenth century saw a wave of reform movements challenging social evils and reviving spiritual traditions.

- Brahmo Samaj (Raja Ram Mohan Roy, 1828) advocated monotheism, women’s rights, and the abolition of sati.

- Arya Samaj (Swami Dayanand Saraswati, 1875) promoted Vedic revivalism and opposed caste discrimination.

- Aligarh Movement (Sir Syed Ahmad Khan) encouraged modern education among Muslims.

- Prarthana Samaj and Theosophical Society worked towards social harmony and spiritual reform.

These movements laid the foundation for modern Indian identity and social justice.

-

Legal and Social ReformsThe British introduced legal measures aimed at curbing social evils and promoting equality. Significant reforms included:

- Abolition of Sati (1829)

- Suppression of Thuggee

- Widow Remarriage Act (1856)

- Age of Consent Acts (1891, 1929)

- Abolition of Slavery (1843)

Although these laws reflected humanitarian ideals, they also provoked conservative resistance, as many Indians perceived them as interference in religious customs.

-

Emergence of New Social ClassesBritish rule created new social groups such as the landed elite, educated intelligentsia, and urban middle class. The introduction of private property, modern professions, and urban centres led to the rise of lawyers, teachers, journalists, and clerks who played pivotal roles in nationalist politics.

At the same time, industrial labour and peasantry became politically conscious, giving rise to trade unions and peasant movements in the early twentieth century.

Cultural and Religious Changes

The exposure to Western culture and rational thought transformed Indian society. The spread of print media, newspapers, and vernacular literature facilitated social debate and national awakening. Writers such as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Rabindranath Tagore, and Premchand used literature to inspire reform and patriotism.

Simultaneously, the British policy of divide and rule accentuated communal divisions. The Partition of Bengal (1905) and the creation of separate electorates for Muslims (1909) deepened communal consciousness, influencing the course of Indian politics in the twentieth century.

Women’s Status and Social Reform

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed significant efforts to uplift women’s status. Reformers like Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Pandita Ramabai, and Sarojini Naidu advocated women’s education and rights. The establishment of girls’ schools and the gradual participation of women in social and political life marked the beginning of gender awakening.

Women played important roles in the Swadeshi Movement, Non-Cooperation Movement, and Quit India Movement, symbolising the social transformation of colonial India.

Overall Impact

British rule in India generated a paradoxical legacy. It introduced modern institutions, communication networks, and the English language, which later aided national integration and political awakening. However, the same rule caused economic impoverishment, social dislocation, and cultural subordination.