Module 102. Biological Classification

Biological classification, also known as taxonomy, is the scientific process of grouping and categorising living organisms based on shared characteristics, evolutionary relationships, and genetic similarities. It provides a systematic framework for identifying, naming, and studying the immense diversity of life on Earth. By organising organisms into hierarchical groups, classification helps scientists understand evolutionary links and predict characteristics shared among different groups.

Historical Background

The practice of classifying organisms dates back to ancient civilisations. The Greek philosopher Aristotle (4th century BCE) made one of the earliest attempts by dividing living organisms into two broad groups: plants and animals. Within animals, he further classified species based on their habitat—land, air, or water. However, this early system was limited in scope and lacked a scientific basis.

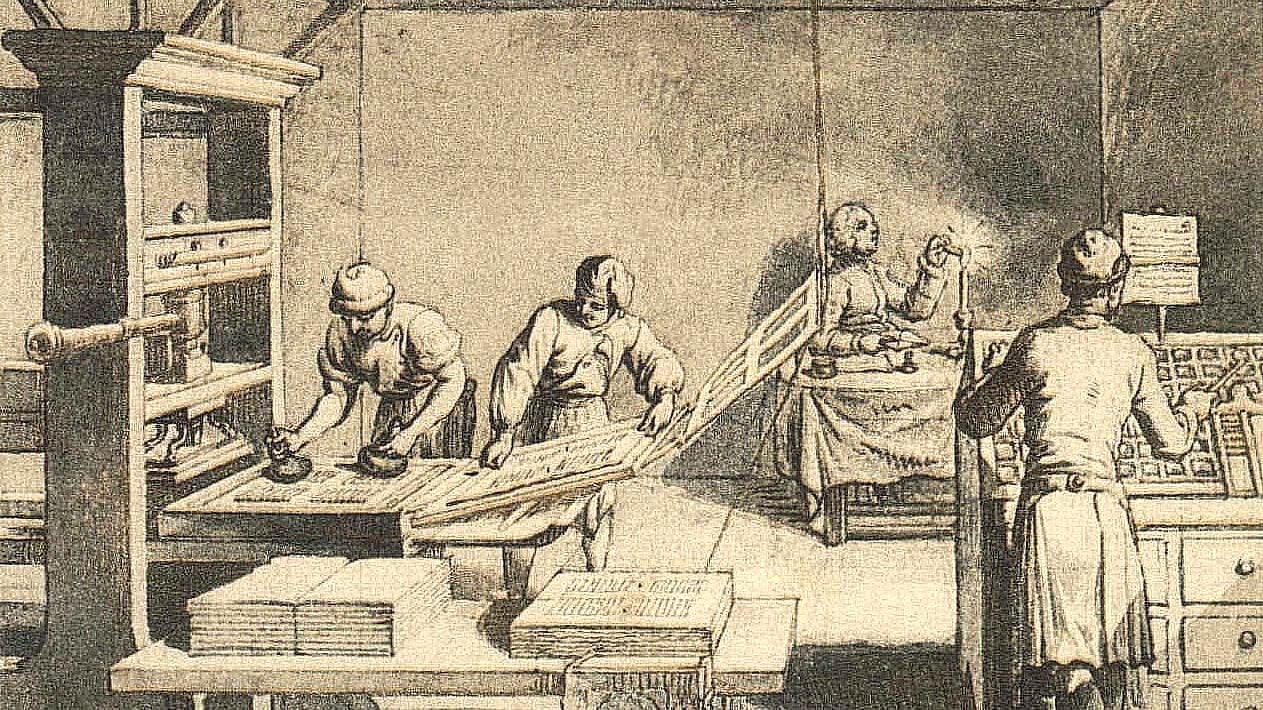

The foundation of modern taxonomy was established by Carl Linnaeus, a Swedish botanist, in the 18th century. In his work Systema Naturae (1735), Linnaeus introduced the binomial nomenclature system, assigning each species a two-part scientific name consisting of its genus and species (for example, Homo sapiens for humans). His hierarchical system—kingdom, class, order, genus, and species—revolutionised biological classification and remains the basis for modern taxonomy.

Subsequent developments, including Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection (1859), profoundly influenced classification by highlighting the importance of common ancestry. Modern taxonomy now incorporates molecular and genetic data, forming a more accurate picture of evolutionary relationships.

Objectives and Importance of Classification

The goals of biological classification are:

- To organise the vast number of known species systematically.

- To provide a universal naming system avoiding regional or linguistic confusion.

- To reveal evolutionary and genetic relationships among organisms.

- To facilitate identification, comparison, and study of living beings.

The importance of classification lies in its ability to unify biological knowledge, supporting disciplines such as ecology, genetics, and conservation biology. It also assists in predicting characteristics of newly discovered organisms based on their related groups.

Hierarchy of Classification

Modern biological classification follows a hierarchical system with several taxonomic ranks. Each rank represents a different level of similarity and relatedness among organisms. The main ranks, from broadest to most specific, are:

- Domain

- Kingdom

- Phylum (for animals) / Division (for plants)

- Class

- Order

- Family

- Genus

- Species

For example, the classification of humans is as follows:

- Domain: Eukarya

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Class: Mammalia

- Order: Primates

- Family: Hominidae

- Genus: Homo

- Species: Homo sapiens

Each lower rank shares more specific features, and the species is the most fundamental unit, representing a group of organisms capable of interbreeding and producing fertile offspring.

Major Systems of Classification

Over time, several systems of classification have been proposed, reflecting advances in scientific understanding.

- Two-Kingdom System (Linnaeus, 1758): Linnaeus divided all living organisms into two kingdoms—Plantae and Animalia. Plants were characterised by autotrophic nutrition and lack of mobility, whereas animals were heterotrophic and mobile. However, this system failed to accommodate microorganisms and intermediate forms such as fungi and protozoa.

- Three-Kingdom System (Haeckel, 1866): Ernst Haeckel introduced a third kingdom, Protista, to include unicellular organisms like bacteria and algae. This was an improvement, yet it still grouped dissimilar organisms together.

- Four-Kingdom System (Copeland, 1938): Herbert F. Copeland proposed a four-kingdom model: Monera, Protista, Plantae, and Animalia, distinguishing prokaryotes (bacteria) from eukaryotes.

-

Five-Kingdom System (Whittaker, 1969): Robert H. Whittaker developed a comprehensive system that remains widely used in biology education. The five kingdoms are:

- Monera: Prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and cyanobacteria.

- Protista: Unicellular eukaryotes like amoeba and algae.

- Fungi: Non-photosynthetic, heterotrophic organisms with chitinous cell walls.

- Plantae: Multicellular, autotrophic organisms with cellulose cell walls.

- Animalia: Multicellular, heterotrophic organisms lacking cell walls.

-

Six-Kingdom and Three-Domain System (Woese et al., 1977): Carl Woese introduced a molecular-based classification using ribosomal RNA sequences. This system divided life into three domains:

- Bacteria (Eubacteria): True prokaryotes with peptidoglycan cell walls.

- Archaea (Archaebacteria): Prokaryotes adapted to extreme environments with distinct biochemical features.

- Eukarya: All eukaryotic organisms, including Protista, Fungi, Plantae, and Animalia.

This three-domain system reflects evolutionary relationships more accurately, forming the foundation of modern phylogenetic classification.

Criteria for Modern Classification

Modern taxonomy uses multiple criteria to classify organisms, integrating morphology, physiology, embryology, ecology, and molecular data. The key approaches include:

- Morphological classification: Based on physical structure and form.

- Anatomical classification: Considers internal organ structure and arrangement.

- Embryological classification: Examines developmental stages and patterns.

- Biochemical classification: Relies on protein, enzyme, and metabolic pathway similarities.

- Molecular classification: Uses DNA and RNA sequencing to determine evolutionary relatedness.

- Phylogenetic classification: Focuses on common ancestry and evolutionary lineage, often represented through phylogenetic trees or cladograms.

The Five Kingdoms: Overview

-

Monera:

- Unicellular and prokaryotic.

- Examples: Escherichia coli, Nostoc, Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- Reproduction: Asexual (binary fission).

-

Protista:

- Mostly unicellular eukaryotes.

- Exhibit autotrophic or heterotrophic nutrition.

- Examples: Amoeba, Paramecium, Euglena.

-

Fungi:

- Multicellular (except yeasts), heterotrophic, with chitin in cell walls.

- Obtain nutrients through absorption.

- Examples: Rhizopus, Penicillium, Agaricus (mushroom).

-

Plantae:

- Multicellular, autotrophic, with chlorophyll for photosynthesis.

- Cell walls composed of cellulose.

- Examples: Mosses, ferns, flowering plants (Rosa, Oryza sativa).

-

Animalia:

- Multicellular, heterotrophic, without cell walls.

- Exhibit movement and complex organ systems.

- Examples: Insects, mammals, birds, humans.

Nomenclature and Identification

Biological nomenclature follows the binomial system established by Linnaeus. The International Code of Nomenclature governs naming conventions, ensuring consistency worldwide. The rules specify that:

- The genus name is written first and capitalised.

- The species name follows and is written in lowercase.

- Both names are italicised (or underlined when handwritten).

For example, Mangifera indica refers to the mango tree, where Mangifera is the genus and indica the species.

Identification involves comparing an unknown organism with described specimens to determine its taxonomic position. This process often employs taxonomic keys, monographs, and field guides.